|

| Image from uncrate.com |

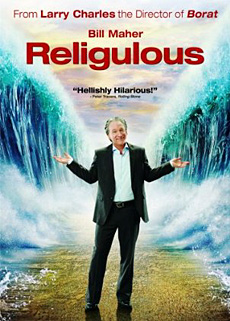

The question of a filmmaker's responsibility to his or her viewer is an oft asked, yet difficultly answered, one. It is a question that was top of mind for me as I watched Bill Maher's Religulous. In this documentary he claims to be going on a search to understand why people follow religions that are based in so much inconsistency and seeming lies. He posits at the beginning of the film that while the bible claims the end of days will one day be upon us, ultimately it will happen because of man's actions and behaviors. He also claims through the opening montage of the film that he will be exploring the three major religions. To a certain extent he a accomplishes this. However he spends about three quarters of the film refuting the words of Christians, while the last quarter is mainly devoted to debunking Muslim doctrine and only 2 short interviews with Jews.

Maher is known for his comedy and political commentary, and it is clear that documentary filmmaking is not his forte. The narrative is often disjointed, not having a clear connection from one point or interview to the next. He jumps around, often not letting the issue to be fleshed out before he moves on or simply mocks the person he's interviewing.

Maher's biggest weakness as documentarian is with his interview skills. He asks his subject a question and then doesn't even let them fully answer the question before he interjects to simply tell them that they're silly or naive for believing what they do. Further, the editing is rather weak as he overly relies on the tactic of leaving the camera on the subject as they squirm uncomfortably, seemingly stumped or merely unsure as to how to answer the question. It also makes it hard to know whether the interviewees are really ignorant on a topic they claim to be experts in or is it simply a function of Maher's editing.

Moreover, Maher claims that he is setting out on a mission to understand religion. He claims over and over that he simply does not understand. However, as the interviews are conducted he does not seem intent on understanding as much as he just wants to prove the other guy to be an imbecile.

Maher interviews a wide variety of individuals, and it's a wonder how he even found many of them. Yet, I personally came to question his honesty in subject choices when it came to the two Jewish interviews. Admittedly, this is the religion I am most familiar with and what I was mostly curious about how he would handle. The first Jewish interview was with a rabbi from a small (and much maligned by mainstream Judaism) group called the Neturei Karta. Members from this group are often found protesting any Israel rallies or Zionist endeavors. They believe that the Jews should not have not be in the land of Israel and they often align themselves with the Palestinians to reinforce their message. Having one member of a fringe subset of ultra-orthodox Judaism stand in for all observant Jews is neither fair nor appropriate in a quest for a supposed understanding of a religion to which he fully admits to not being educated in.

The other Jewish interview he conducts is with an engineer who creates items which gets around certain legal prohibitions of the sabbath so certain items can be used. And yes, while some of the loopholes are a bit extreme, he neglects to mention the minutiae of why it is permitted and under what circumstances. For instance the ridiculous looking phone he highlights is not simply to allow observant Jews to call one another to shoot the breeze on the sabbath, but rather in emergencies where the phone might otherwise not be permitted. Seeing the dishonesty in his storytelling in these instances highlighted for me the possibility and probability of him having done the same for the other religions.

The documentary filmmaker is not a journalist and is not legally or even officially bound to a set of ethical standards. However, they have generally taken it upon themselves to abide by honest rules of storytelling to ensure the trust of their viewers and subjects. It's in this arena Maher should take a lesson. His film making and storytelling would benefit greatly if he did so with an ounce of humility and honesty. He asserts himself as the voice of reason and. Often does make interesting points that should be asked and discussed by and "believer." Yet if he were truly interested in understanding his subject matter he would much benefit by allowing he interviewees speak their piece.

3 comments:

Part I

The trouble with Maher's documentary is that it is intended more to ridicule religious faith and practice than it is an attempt to understand religiosity. Maher enters the film a skeptic, which is not in and of itself a problem except for that he considers himself intellectually superior to the subjects in his film. What is more, Maher focuses his attention on fringe elements of the faiths he is trying to (ostensibly) portray. Of all the religions presented in the film, Christianity fares the worst. Maher's theological critiques are worth considering, as it is irrational to believe in miracles and other wonders recorded in the New Testament (or the Torah, Qur'an, the Vedas, etc). These theological issues have been furiously debated over within all the religions presented in the film themselves, and critiques such as Maher's add nothing new to the discourse.

Yet the crucial problem lies not with Maher's doubt, but his inability to comprehend religiosity as a domain in which those endowed with even a shred of intellect can partake in. Surely, the "truck stop" Christians live less sophisticated and cosmopolitan lives than does Maher, but it would appear from his film that these individuals lack mental prowess, and therefore should not be taken seriously. This is most likely the result of clever editing on the part of Maher to sway the viewer to sympathize with Maher's thesis: Religion is almost as stupid as its adherents. We also have the issue of Maher's documentary approach, namely, going to the most fringe elements of a religion in order to showcase the most extreme and "looney" forms of the three Abrahamic religions. This is not only poorly indicative of the state of those religions today, but is intellectually dishonest. It is simply unreasonable to portray Christianity, for example, as a religion which caters to those who engage in glossolalia and creationism. Not all streams are alike, and not all adherents can be painted with the same brush. Ironically, a Vatican priest working for the Vatican Observatory is interviewed and explains how the Vatican acknowledges scientific discovery and scientific interpretation. Although Maher includes this interview in his film, this reality does not temper his criticism of the irrationality of religious adherents.

Part II

Maher also has the unfortunate habit of interrupting those he is interviewing and finding any opportunity to mock them without allowing them to speak their minds. Although what some of them may have to say may be utter rubbish, what they may say may equally be enlightening. Having the attitude that one has all the answers and nothing to learn makes for a very poor interview and an even less convincing argument. Maher's mockery of biblical stories, often thrown out haphazardly and out of context to support his thesis on the ridiculousness of religion and religiosity, only frustrates the interviewee, amuses the viewer for its comedic effect (not necessarily for its rudeness) but does not do justice to the actual conversation that needs to be had about religion.

Stepping back for a moment, it would be fair to also state that the goal of the film was most likely to entertain rather than to educate. Were the film an actual exercise in education, there would probably be a fairer account of religion, its origins, history, principles, etc. This, however, does not absolve the film from doing more harm than good. The film make several errors in certain regards:

a) It seeks to remove the right of religious people from the public discourse by asserting that they are unfit to make decisions surrounding public life;

b) It assumes that non-religiosity, or rather, an orthodox atheism is a desirable solution to the "status quo" of religiosity in public life;

c) It alienates religious people, and even non-believers who take a more tempered attitude toward the debate over religion and state;

d) At a base level, it humiliates a group of individuals, who do not necessarily represent the movements they are made out to represent. A humiliation which is then extended upon a group of individuals claiming to be of that faith group, but not of that orientation.

One example of this is Maher's treatment of Orthodox Judaism. He interviews a member of the radical sect "Neturei Karta," a staunchly anti-Zionist (and in some cases, ironically, anti-Semitic) Hasidic sect, which is reviled by nearly the entire Jewish world, to hear their views on Israel. Now, I can't help but admit that I enjoyed hearing Maher criticize what I consider to be NK's perverse theological and political views, but I could not help but wonder why he would approach the most radical of the radical elements to portray as a Jewish archetypical figure. NK does not accurately portray Judaism or the Jewish people. They are the fringe of the fringe. It would be equivalent to interviewing the Taliban in order to learn more about Sufi Islam. The two are not analogous and are ideologically at odds, despite being of the same religious heritage. Clearly, this was an exercise done to buttress the appeal of the film, and not to contribute to some genuine intellectual discourse on religion and religiosity.

I could continue this debate, but I would like to finish off with a discussion regarding atheism and its relation to the film. Maher is justified in asking for evidence to prove the truth of religion. The underlying subtext and the crux of the film's argument - when unearthed and dusted off from the cinematic aspects of the film - is an important argument to be had. How do we know religion is true? Is there a god? Which religion is the right one if there is a god? How should religion play out in the public sphere? All of these are questions that have been asked, are being asked, and will continue to be asked in the future. Religion has yet to answer these in a sufficient way to satiate the curiosity of the atheist, nor is it likely religions will ever be able to offer any concrete evidence for a god or gods. The atheist is right to question, is right to ponder, and is right to want more than just a threat of hellfire, or convoluted attempts at using science to validate scripture to force belief upon an unwilling individual.

Part III

On the other hand, atheists need to recognize that atheism is not necessarily a force for good (and neither is religion) in the world simply because it seeks to subdue religion and render it null and void. Atheism lacks the sense of community and moral drive that religion provides. That is not to say that any moral claim or principle made by religion is not problematic - there are many things that religions consider "moral," which to others would be equally reprehensible. Moreover, religion has done much harm in the past, but has also, despite protest to the contrary, done great things for mankind and inspired evil as well good in the world. What I mean to say here, is that atheism is simply a lack of belief, but does not in and of itself carry a moral compass. There are atheist liberals, communists, fascists, libertarians, isolationists, universalists, and any other ideology under the sun. Atheists tend to get their moral compass from ideologies that stand for some ideal or another (including moral principles inherited from religion). Atheism, in and of itself, is not a moral code, or a set of principles or ethics, but is simply the absence of belief in the supernatural, with no particular moral consequence assigned to such disbelief. "Freethinkers" like Maher, should focus their time and energy in improving the political, economic and social problems of their communities rather than focusing on the exaggerated evils of religion and religiosity. A similar documentary could be produced about the evils of the militant atheism of the Soviet Union, for example, but this would simply be a misrepresentation of the vast majority of law-abiding, tax-paying, kind, loving and well-meaning atheists the world over. Perhaps, a documentary on the abuse of "ideologies," be they religious or otherwise, would be a more useful service to the public and the debate over how to improve governance the world over.

Post a Comment